Even After

the Gulf War, the U.S. helped Saddam Hussein stay in power.

"Notice

that contrary to the line that’s constantly presented

about what the Gulf War was fought for, in reality

it had nothing to do with not liking Saddam Hussein

- as can very easily be demonstrated. So just take

a look at hat happened right after the U.S. bombardment

ended. A week after the war, Saddam Hussein turned

to crushing the Shiite population in the south of

Iraq and the Kurdish population in the north: what

did the United states do? It

watched. In fact, rebelling Iraqi generals

pleaded with the United States to let them use captured

Iraqi equipment to try to overthrow Saddam Hussein.

The U.S. refused. Saudi

Arabia, our leading ally in the region, approached

the United States with a plan to support the rebel

generals in their attempt to overthrow Saddam after

the war: the Bush administration blocked the plan,

and it was immediately dropped." [see footnote]

( p168 Understanding

Power Noam Chomsky ) "Notice

that contrary to the line that’s constantly presented

about what the Gulf War was fought for, in reality

it had nothing to do with not liking Saddam Hussein

- as can very easily be demonstrated. So just take

a look at hat happened right after the U.S. bombardment

ended. A week after the war, Saddam Hussein turned

to crushing the Shiite population in the south of

Iraq and the Kurdish population in the north: what

did the United states do? It

watched. In fact, rebelling Iraqi generals

pleaded with the United States to let them use captured

Iraqi equipment to try to overthrow Saddam Hussein.

The U.S. refused. Saudi

Arabia, our leading ally in the region, approached

the United States with a plan to support the rebel

generals in their attempt to overthrow Saddam after

the war: the Bush administration blocked the plan,

and it was immediately dropped." [see footnote]

( p168 Understanding

Power Noam Chomsky )

|

|

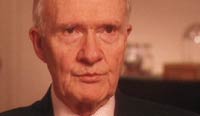

Brent Scowcroft

served as national security adviser in the George H.

W. Bush administration. In this interview he discusses

why Saddam Hussein is a separate problem from going

after bin Laden's terrorist network, explains why the

coalition against terrorism is even more important than

the coalition built during the Gulf War, and defends

the decision in the earlier Bush administration not

to go after Saddam at the end of the Gulf War

and not to support uprisings in the northern and

southern parts of Iraq. He was interviewed in

October 2001.

Interviewer:

We didn't cut off their

gasoline supplies.

Brent Scowcroft: First

of all, one of our objectives was not to have Iraq split

up into constituent ... parts. It's a fundamental interest

of the United States to keep a balance in that area,

in Iraq. ...

Interviewer:

So part of the reason

to not go after his army at that point was to make sure

there was a unified country, whether or not it was ruled

by Saddam?

Brent Scowcroft:

Well, partly. But suppose we went

in and intervened, and the Kurds declare independence,

and the Shiites declare independence. Then do we go

to war against them to keep a unified Iraq?

Interviewer: But why would

we care at that point?

Brent Scowcroft: We

could care a lot.

Interviewer: I

thought we had two interests. One was to evict the Iraqi

Army from Kuwait. But the other really was to get Saddam

out of power.

Brent Scowcroft:

No, it wasn't.

Interviewer:

Well, either covertly

or overtly.

Brent Scowcroft:

No. No, it wasn't. That

was never... You can't

find that anywhere as an objective, either in the U.N.

mandate for what we did, or in our declarations, that

our goal was to get rid of Saddam Hussein.

Link:

PBS

- frontline: gunning for saddam: interviews: brent scowcroft

|

|

footnote:

On the rebel Iraqi generals' rejected pleas, see for example,

John Simpson, "Surviving In The Ruins," Spectator

(U.K.), August 10, 1991, pp. 8-10. An excerpt: "Our

programme [Panorama on England's B.B.C.-1] has found evidence

that several Iraqi generals made contact with the United

States to sound out the likely American response if they

took the highly dangerous step of planning a coup against

Saddam. But now Washington faltered. It had been alarmed

by the scale of the uprisings [against Saddam Hussein] in

the north and south. For several years the Americans had

refused to have any contact with the Iraqi opposition groups,

and assumed that revolution would lead to the break-up of

Iraq as a unitary state. The Americans believed that the

Shi'as wanted to secede to Iran and that the Kurds would

want to join up with the Kurdish people of Turkey. No direct

answer was returned to the Iraqi generals; but on 5 March,

only four days after President Bush had spoken of the need

for the Iraqi people to get rid of Saddam Hussein, the White

House spokesman Marlin Fitzwater said, "We don't intend

to get involved . . . in Iraq's internal affairs. . . ."

An Iraqi general who escaped to Saudi Arabia in the last

days of the uprising in southern Iraq told us that he and

his men had repeatedly asked the American forces for weapons,

ammunition and food to help them carry on the fight against

Saddam's forces. The Americans refused. As they fell back

on the town of Nasiriyeh, close to the allied positions,

the rebels approached the Americans again and requested

access to an Iraqi arms dump behind the American lines at

Tel al-Allahem. At first they were told they could pass

through the lines. Then the permission was rescinded and,

the general told us, the Americans blew up the arms dump.

American troops disarmed the rebels."

|

Jim

Drinkard, "Senate Report Says Lack of U.S. Help Derailed

Possible Iraq Coup," A.P., May 2, 1991 (Westlaw database

# 1991 WL 6184412). An excerpt: "Defections by senior

officials in Saddam Hussein's army -- and possibly a coup

attempt against Saddam -- were shelved in March because the

United States failed to support the effort, according to a

Senate Foreign Relations Committee staff report. . . . [T]he

United States "continued to see the opposition in caricature,"

fearing that the Kurds sought a separate state and the Shi'as

wanted an Iranian-style Islamic fundamentalist regime, the

report concluded. . . .

"The public snub of Kurdish and other Iraqi opposition

leaders was read as a clear indication the United States did

not want the popular rebellion to succeed," the document

stated. . . . The refusal to meet with the Iraqi opposition

was accompanied by "background statements from administration

officials that they were looking for a military, not a popular,

alternative to Saddam Hussein," the committee staff report

said. . . . The United States resisted not only the entreaties

of opposition figures, but of Syria and Saudi Arabia, which

favored aiding the Iraqi dissidents militarily, the report

contended." |

A.P.,

"Senior Iraqis offered to defect, report says," Boston

Globe, May 3, 1991, p. 8; "Report: U.S. Stymied Defections,"

Newsday (New York), May 3, 1991, p. 15; A.P.,

"Senior Iraqis offered to defect, report says," Boston

Globe, May 3, 1991, p. 8; "Report: U.S. Stymied Defections,"

Newsday (New York), May 3, 1991, p. 15;

Tony Horwitz, "Forgotten Rebels: After Heeding Calls To Turn

on Saddam, Shiites Feel Betrayed," Wall Street Journal Europe,

December 31, 1991, p. 1.

For more

on the immediate decision by the U.S. to allow Saddam Hussein

to massacre the rebelling Shiites and Kurds -- in part using attack

helicopters, as expressly permitted by U.S. commanders -- at the

conclusion of the Gulf War, see for example, Michael

R. Gordon and General Bernard E. Trainor, The

Generals' War: The Inside Story of the Conflict in the Gulf,

Boston: Little Brown, 1995, pp. 446-456 (on Saudi Arabia's rejected

plan to assist the Shiites who were trying to overthrow Saddam,

see pp. 454-456). For more

on the immediate decision by the U.S. to allow Saddam Hussein

to massacre the rebelling Shiites and Kurds -- in part using attack

helicopters, as expressly permitted by U.S. commanders -- at the

conclusion of the Gulf War, see for example, Michael

R. Gordon and General Bernard E. Trainor, The

Generals' War: The Inside Story of the Conflict in the Gulf,

Boston: Little Brown, 1995, pp. 446-456 (on Saudi Arabia's rejected

plan to assist the Shiites who were trying to overthrow Saddam,

see pp. 454-456).

(from footnotes

for Chapter 5 of Understanding

Power Noam Chomsky

|